Secondary stroke prevention: an occupational therapy program

In the United States, a stroke occurs approximately 800,000 individuals annually, accounting for a large population of severe long-term disabilities (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2021). In the United States, 25% of all strokes, approximately 610,000, occur among those individuals who have already had a previous stroke, raising the risks of long-term disability (CDC, 2021). NORD (2020) reports stroke recurrence leads to poorer functional outcomes, quality of life, and increased incidence of mortality. Stroke recurrence affects a large population, so reducing secondary stroke is essential to reduce mortality and disability risks.

Secondary stroke prevention refers to interventions and education to mitigate the risks of stroke recurrence. Secondary stroke prevention focuses on reducing the risk of stroke recurrence. Lifestyle changes can improve modifiable risk factors. Indeed, stroke education is a Centers for Medicare/Medicaid (CMS) requirement of clinicians in hospital settings. However, preventative education offered by therapists to stroke survivors, especially those with secondary diagnoses of stroke, is not optimal (Perry et al., 2020). According to Diener et al. (2020), approximately 90% of strokes are preventable and attributed to modifiable risk factors, with hypertension being the most impactful element. Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is the fifth leading cause of death in the United States and contributes to one-third of strokes (CDC, 2021; Diener et al., 2020). Compared with those with normal blood pressure, people with hypertension are four times more likely to have a stroke (Tibebu et al., 2021).

There is a need for more evidence regarding practical and tangible solutions for stroke survivors (Jucket et al., 2021). Despite stroke education provided to patients in the hospital setting, as required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, there continues to be poor retention of stroke education (Johnson et al., 2018). Education is lengthy and can be overwhelming. Clients and caregivers must take in information on what a stroke is, the impact it had and will have on the client, the causative pathogenesis, additional risk factors, medication management, and adherence to treatment protocols. Other barriers to education for stroke prevention include lack of health literacy, interest from patients and caregivers, and time (Perry, 2020).

Occupational therapists (OTs) know about lifestyle development, environmental modifications, and habits that can improve stroke clients’ health (Malstam et al., 2021). OTs must consider client factors to support patient autonomy when introducing necessary lifestyle changes to prevent the second incidence of strokes (Carter et al., 2020). Integrating everyday living with healthy behavior changes presents greater functional independence and quality of life (Hill et al., 2019). Optimal stroke prevention requires a balanced, integrated approach emphasizing education on stroke risk and healthy lifestyle behaviors. With knowledge of simple screening, modifiable and treatable risk factors can be managed (Diener et al., 2020).

The Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) and Health Behavior Model (HBM) embody lifestyle management for stroke prevention. The integration of these two models can be used to develop an occupation-based program focusing on improving the relationship between disease management and self; in this case, the self is the stroke survivor. The primary focus of MOHO is to address how and why we, as humans, engage in occupational behavior. It also addresses how we modify our occupations as we interact with our environment. This dynamic, open-cycle system of human actions is an exciting model. The model states three interrelated parts to each person: volition, habituation, and performance skills (Kielhofner & Burke, 1980). HBM helps one understand the perception of self-efficacy through increased education. One of the critical elements of the HBM is to predict health-related behaviors. The model defines health behavior factors with an individual’s perceived susceptibility (risk threat), severity, benefit, obstacles to action, cues to action, and self-efficacy (Rural Health Information Hub, 2018).

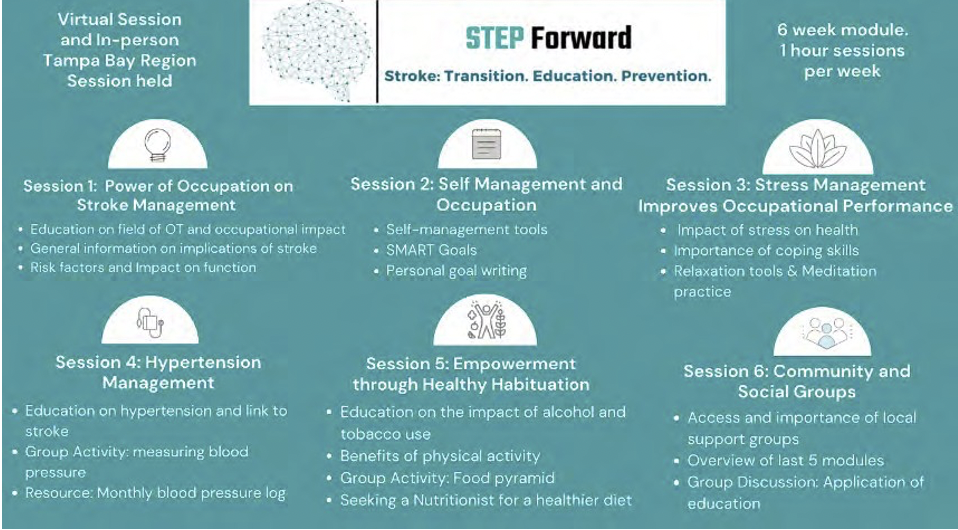

An Occupation-based program, Step Forward, was created and implemented as an OTD capstone project (Figure 1). The program was created and administered to promote health, wellness, and well-being for individuals post-stroke, providing education and resources for secondary stroke prevention. Participants of this program included stroke survivors and caregivers of stroke survivors.The program focused on building sustainable lifestyle habits to reduce modifiable risk factors through education, demonstration, and self-reflection. This program intends to help individuals engage in health management in meaningful and sustainable ways.

Figure1:Step Forward- Occupation-Based Program for Secondary Stroke Prevention(below)

The STEP Forward program was created to showcase that community-based OT programs can be impactful in educating stroke survivors in lifestyle modification to reduce risk factors. The program followed an occupational therapy-based model, MOHO, with an overlap of the health belief model. Each session provides evidence-based, occupation-based, and client-centered methods to improve occupational engagement and create lifestyle changes.

References

Carter, Robinson, K., Forbes, J., Walsh, J. C., & Hayes, S. (2019). Exploring the perspectives of stroke survivors and healthcare professionals on mobile health to promote physical activity: A qualitative study protocol. HRB Open Research, 2(9), 1-12. https://doi. org/10.12688/hrbopenres.12910.1

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2021). Stroke. https://www.cdc.gov/stroke/index.htm

Diener, & Hankey, G. J. (2020). Primary and secondary prevention of ischemic stroke and cerebral hemorrhage: JACC focus seminar. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 75(15), 1804–1818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.072

Hill, V., Miller, V., & Towfighi, A. (2019). Feasibility of a community-based OT-led life-management intervention for individuals with stroke. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(4_Supplement_1), 7311515364p1. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2019.73S1-PO5032

Johnson, B., Handler, D., Urrutia, V., & Alexandrov, A. W. (2018). Retention of stroke education provided during hospitalization: Does provision of required education increase stroke knowledge?. Interventional neurology, 7(6), 471–478. https://doi.org/10.1159/000488884

Juckett, Wengerd, L., Faieta, J., & Griffin, C. (2018). Analyzing strategies for implementing evidence-based practice in stroke rehabilitation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 99(10), e116– e116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2018.07.413

Kielhofner, G., & Burke, J. P. (1980). A model of human occupation, part 1: Conceptual framework and content. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 34(9), 572-581.

Mälstam, E., Asaba, E., Åkesson, E., Guidetti, S., & Patomella, A.H. (2022). “Weaving lifestyle habits”: Complex pathways to health for persons at risk for stroke. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 29(2), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2021.1903991

NORD. (2022). National Stroke Association. https://rarediseases.org/ organizations/national-stroke-association/

Perry, Billek-Sawhney, B., & Schreiber, J. (2020). Stroke prevention: Education and barriers for physical and occupational therapists caring for older adults. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 38(4), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703181.2020.1755410

Rural Health Information Hub. (2018). The Health Belief Model. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/health-promotion/2/theo-ries-and-models/health-belief

Tibebu, Emiru, T. D., Tiruneh, C. M., Nigat, A. B., Abate, M. W., & Demelash, A. T. (2021). Knowledge on prevention of stroke and its associated factors among hypertensive patients at Debre Tabor General Hospital: An institution-based cross-sectional study. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 14, 1681–1688. https://doi.org/10.2147/RMHP.S303876